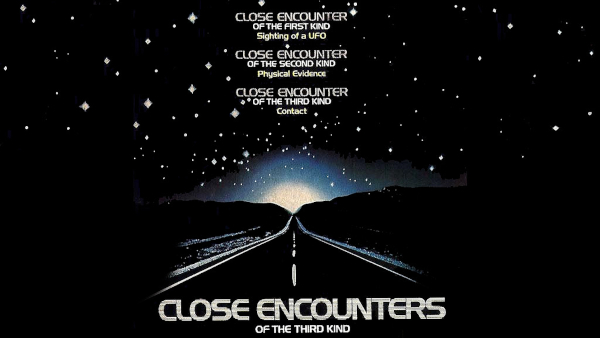

Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977)

moviesreviewsscifi

Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) is one of Steven Spielberg's most well-known and celebrated films, following in the path of his blockbuster Jaws (1975).

It's hard to find a film that so captures the zeitgeist of the late Seventies as Close Encounters. As a kid growing up in the UK, one of the favorite books on my shelf was Usborne's World of the Unknown: UFOs which came out in the same year as Close Encounters. This book was part of a series which included monsters (Bigfoot, the Loch Ness Monster, and so on) and ghosts, but the one on UFOs was my personal favorite. I became a local expert on the Roswell crash and the Hopkinsville Goblin. Of course I believed the theories of Erich von Däniken that aliens built the pyramids of Egypt and engraved the Nazca lines of Peru, and that Project Blue Book was a government cover-up. The Bermuda Triangle held a particular fear and fascination for children at the time - any plane or boat travelling from Miami to the Bahamas was in danger of being snatched by a passing UFO or sucked into the depths of the ocean by a mysterious vortex (the Bermuda Triangle, of course, has some passing references in this film).

Belief in the UFOs went hand-in-hand in this period with a fascination for all things occult and paranormal. Films such as The Exorcist, The Omen and Carrie scared audiences with Satanism, witchcraft and psychic powers; TV shows presented by such serious figures from science fiction as Arthur C Clarke and Leonard Nimoy talked of ancient aliens long before it was a History Channel meme and gravely posed the question of whether the Sasquatch was real over grainy footage of what appeared to be a man in Chewbacca cosplay sitting on a log. In those halcyon pre-Internet days we pored over books and magazines covering subject matter from psychic auras to Tarot cards to spontaneous combustion.

Close Encounters not only played into the paranormal craze but another mood of the times, particularly in the United States. The Watergate hearings and the Vietnam War had ended a few short years before. Americans, particularly the younger generation, had lost trust in their government and conspiracy theories, previously the domain of the lone nutter and John Birch Society newsletter subscriber, went mainstream. Films such as The Parallax View, Network and 12 Days of the Condor implied that the government was manipulated from behind the scenes by a shadowy cabal. In Close Encounters the US military and UN create a cover story while secretly in contact with the aliens. It's unclear what their motivations are, but unlike the extraterrestrials they do not appear benign. These intertwining themes of government conspiracy and the paranormal would have a very long cultural shelf-life, from the X-Files in the 1990s through to the Internet conspiracies and urban myths of today.

Extraterrestrial paranormal activity and shadowy government conspiracies alone would have been grist for the mill of a great Seventies science fiction movie, but the secret of Spielberg's genius was never just in the big themes and cinematic experiences. As with Jaws and later films such as ET and Poltergeist, Spielberg tells his story through the eyes of ordinary people and families.

Richard Dreyfuss, who had previously worked with Spielberg in Jaws, is a working-class man, Roy Neary, employed at a local power company in the Mid-West (the story takes place in Indiana, Ohio and Wyoming). We first see him with his wife Ronnie (Teri Garr) and their three children. It is not an harmonious household - the children are misbehaving, Ronnie is nagging Roy and the kids, and Roy is trying to interest the kids in going to see Pinocchio. Roy seems already somewhat tuned out from his family and it's clear from his loving description of Pinocchio that he is in early mid-life crisis, looking back nostalgically at a childhood movie. Today we look back at the 1970s with a nostalgic eye, but the 1970s was also deeply mired in nostalgia for the 1950s and early 60s, particularly as the Baby Boomer generation started entering adulthood and all its responsibilities. It's not surprising that shows such as Happy Days and films such as Grease and American Grafitti were also big hits in this era. Spielberg was of this generation and attuned to its moods; Close Encounters is as much a story of a man looking to return to the innocence and wonder of childhood as it is about first contact with aliens. Towards the end of the movie you can hear the tune of When You Wish Upon a Star, sung by Jimmy Cricket in the 1940 Pinocchio adaptation; Ronnie semi-mockingly called Roy "Jimmy Cricket" when he was trying to talk the kids into going to see Pinocchio.

We also witness another family unit, single mum Jillian (Melinda Dillon) living alone in a country house with her four-year old son Barry. Barry, like Ray, has a childlike fascination for the aliens (unlike Ray of course, he's an actual child). Barry's abduction by the aliens drives Jillian and Ray together in their quest for the truth.

Interspersed with the family drama of ordinary Americans in extraordinary circumstances are scenes of a UN investigation team, chasing clues of alien visitation around the world, from a squadron of 1940s bombers appearing in the Mexican desert (keen Bermuda Triangle enthusiasts will recognize the planes from Flight 19, which vanished off the Florida coast in 1945) and a ship in the middle of the Gobi (the USS Cotopaxi, another real-life disappearance actually resolved by the discovery of its wreck in 2020).

The team encounter a crowd of religious worshippers in India, who have apparently witnessed a UFO. The crowd are chanting a musical sequence they heard broadcast from this spacecraft. This sequence - the film's signature motif - is later received by a radio telescope and decoded as a set of coordinates - the location of Devil's Tower, a mysterious natural geological structure in the Wyoming prairie. The team is led by legendary French director François Truffaut, supported by his hard-working interpreter (Bob Balaban).

Ray and other everyday folk are also drawn to Devil's Tower - not by radio signals from space but through unexplained psychic visions of the mountain they are compelled to sculpt in clay and mashed potato. These chosen ones - ordinary citizens, not soldiers or scientists - attempt to reach Devil's Tower despite a government story of a chemical spill and being pursued by the inevitable black helicopters.

The culmination at Devil's Tower - first contact with the aliens - plays out like a Jean Michel Jarre light show, with musical sequences repeated back and forth between the humans and ETs to establish communication. The mothership finally descends, a huge spacecraft lit up like giant Christmas tree, and the extraterrestrial beings emerge, bathed in light. The aliens seem to be of different species, some tall and spindly, others small, almost child-like, reminding us again of Ray's desire to return to childhood innocence. Barry is returned to his mother along with other humans abducted over decades (unaged thanks to relativistic space travel). The aliens take Ray by the hand into the mothership and it ascends to the heavens. Ray begins his long interstellar voyage (the moral conundrum of a man essentially abandoning his family to pursue his dream is never raised; we can assume the child support agency's remit does not reach beyond Earth orbit).

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is perhaps one of the best science fiction films of the 1970s and a classic that has stood the test of time. It firmly established Steven Spielberg as one of the great film-makers and storytellers of his generation. John Williams provides one of his iconic scores and a talented cast add an essential human element to the story.

- Next: Django, HTMX and Alpine